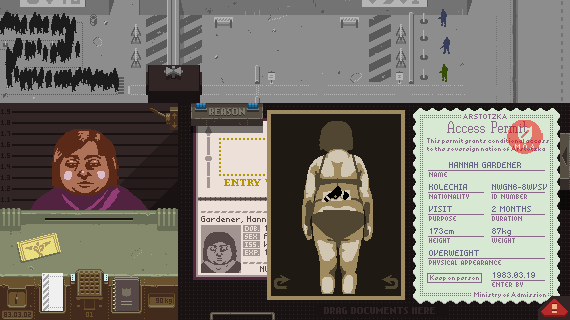

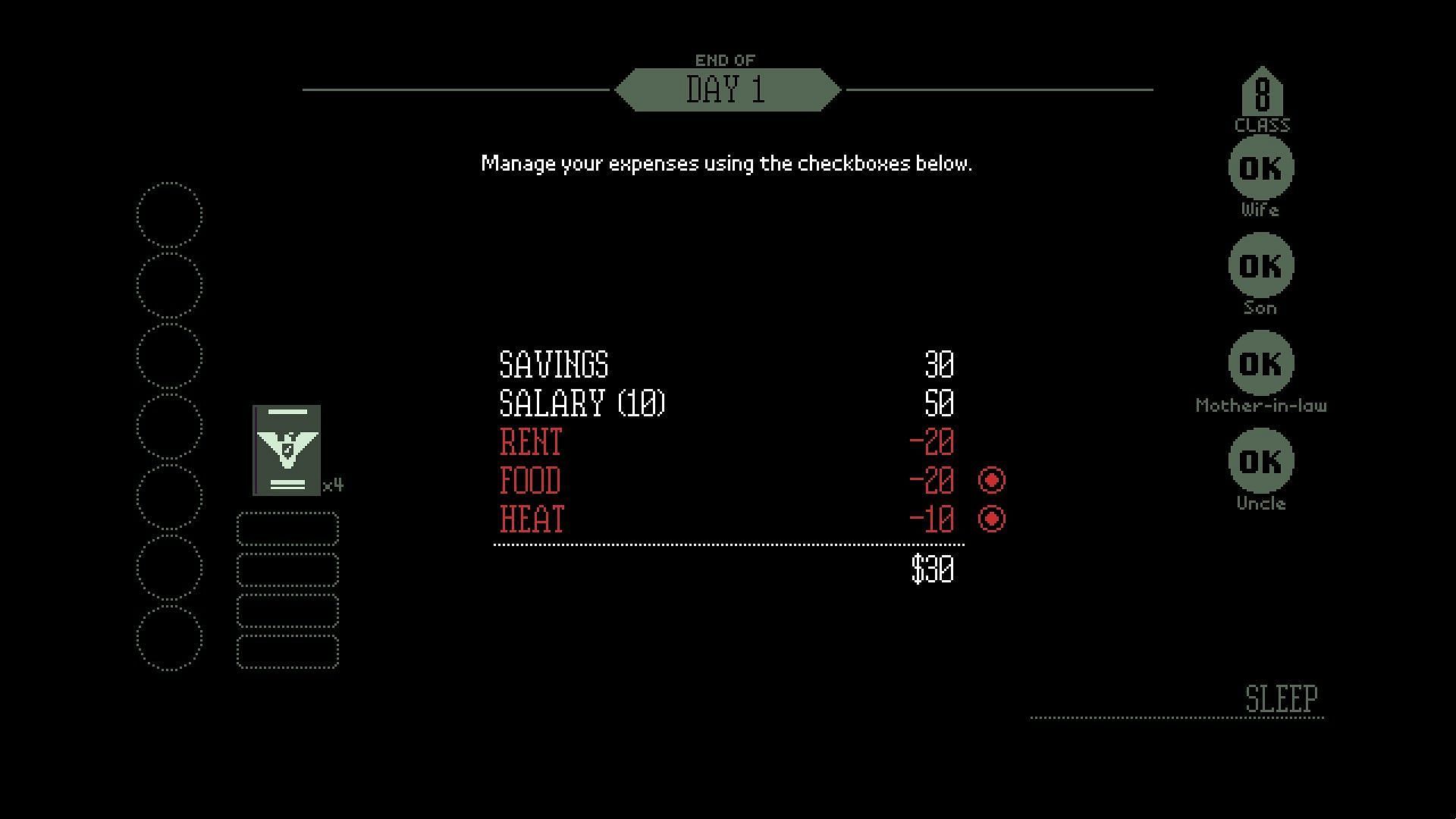

The raw material you’re processing is people. Therein lies the problem and the deeper message of Papers, Please. Setting up and executing efficient procedures is rewarding, both in terms of in-game currency and in that portion of your brain that likes processing chaos and refining it into order. Success in Papers, Please bestows the same satisfaction games like Diner Dash or The Sims do. Even the way you physically array a collection of documents can obscure a crucial piece of information at the bottom of a heap of papers.

Unless you have a good memory, you’ll be leafing through the rulebook and daily policy change notices to double check passports for discrepancies. Each document must be manually dragged from the counter to your inspection table. Things look bland, but they feel frantic as you try to make evaluations both quickly and carefully. As a border agent, you get paid for each person you let through, but you’re docked pay for mistakes, so you don’t really want to spend more time than absolutely necessary on any one person. The game’s drab colors, plodding music, and over all down-trodden environment set the tone for a process that rewards emotional detachment. However, as the game goes on, the human cost of of your decision for both you and those you evaluate becomes apparent, leading to some uncomfortable realizations about the power of social structures. Your job is simple: grant or deny people passage to the country. It’s a game where you play as an immigration inspector who has to process paperwork and make the decision whether to allow people to cross the border. Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please offers one possible explanation, albeit one set in a much more dramatic environment. What was going through her mind while she looked at our documents? The seconds it took for her to reach for her stamp felt like years. Still, watching the border officer review all our paperwork was tense.

were fairly navigable in the grand scheme of things. We weren’t going to be secreted away by fascist goons, and the laws of both the U.S. We had given up our apartment and jobs in the U.S., but if we got denied, we still had friends and family to help us out.

I can recall very few situations more stressful than that customs line: Did I have all my papers? What questions were they going to ask? What would happen if I got waived through but my wife didn’t? In terms of “immigrations,” it was a relatively mild one.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)